down syndrome occurs when an embryo inherits an extra copy of chromosome 21, leading to overexpression of the genes it carries.1 Scientists have yet to explore how these extra gene copies drive Down syndrome, but a team of geneticists led by Katherine Waugh of the University of Colorado recently revealed the role four interferon receptor genes play. In a mouse study published in Genetics of natureoutlined the influence of these genes, suggesting that it may become possible to alleviate the co-conditions of Down syndromes by blocking interferon signalling.2.3

I’m not trying to fix Down syndrome or prevent it, Waugh said. I am trying to help everyone with Down Syndrome live a happier and healthier life.

Interferons are proteins secreted by cells that signal the immune system to fight cancer and infection.4 Extra copies of interferon receptors boost interferon signaling in the cells of people with Down syndrome, but it wasn’t clear whether this contributed to the developmental changes.5

See also Why viral infections are more severe in people with Down syndrome

Looking for a causal link, the researchers turned to the Dp16 mouse model of Down syndrome. It is difficult to model Down syndrome since the genes on human chromosome 21 are distributed across three different chromosomes in mice. Mouse chromosome 16 carries the largest fraction of these genes, 120 of which have extra copies in mouse Dp16, including the cluster of four interferon receptor genes that Waugh wanted to explore. Dp16 is less severe than other mouse models of Down syndrome, and Waugh noted that these mice vary in the characteristics they display, mimicking well the range of severity seen in people with the syndrome.

Using CRISPR-Cas9 technology, the team deleted four interferon receptor genes in Dp16 mice to determine whether they contribute to developmental changes. We knocked 192 kilobases off a chromosome in the mouse, which is no small feat these days, and it certainly wasn’t when we embarked on this process years ago, said Kelly Sullivan, a researcher at the University of Colorado and co-author of the study.

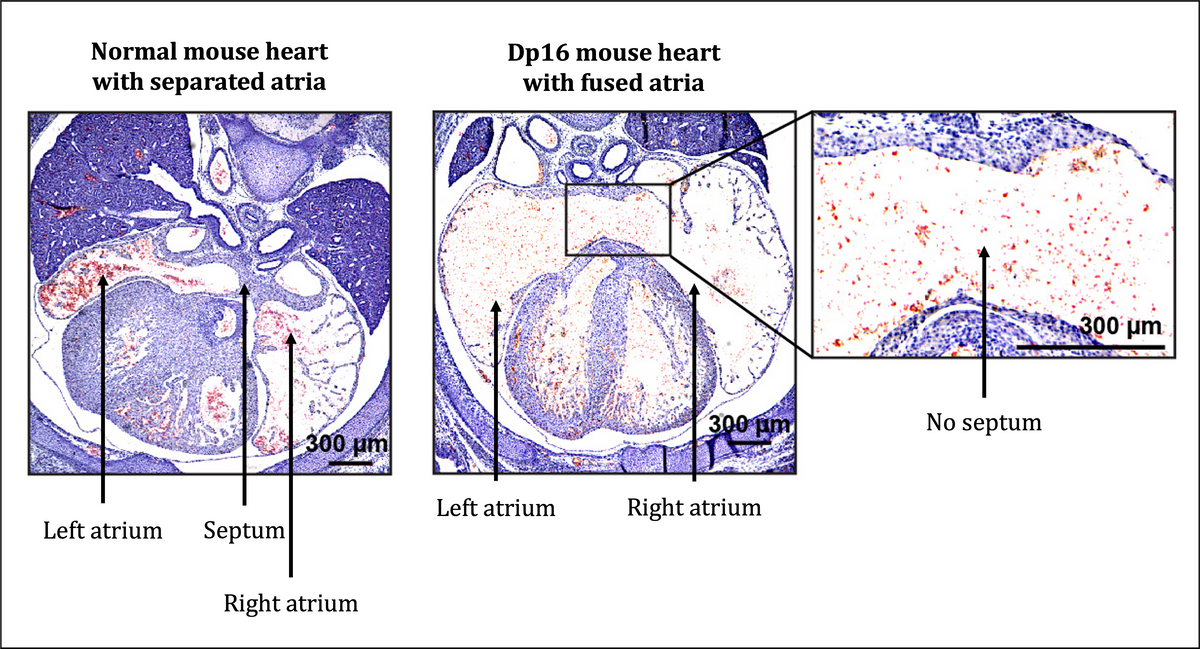

The Dp16 mice experienced various developmental changes in the heart, such as the fusion of the left and right atria. The team showed that the interferon receptor genes were to blame for this aberrant development as mice lacking the extra genes were less likely to develop these heart conditions. Deleting these genes also prevented developmental changes in the brain and skull that were common in the model, including eye twitching and a short skull.

Fused atria are one of the developmental changes found in hearts taken from mouse models of Down syndrome.

The team also tested the cognitive abilities of the mice as learning and memory are commonly affected in people with Down syndrome.6 The researchers challenged the mice to locate a hidden platform in a circular tank filled with water. The position of the platforms changed before each session, and the team determined how quickly the mice recorded this change by tracing their swimming paths.

For Joaquin Espinosa, a researcher at the University of Colorado and co-author of the study, Dp16 mice with the extra interferon genes learned more slowly to avoid checking previous location, indicating that the extra gene copies are linked to cognitive impairment.

These conditions were only partially restored by knocking out the extra genes, suggesting that extra copies of other genes also contribute to the phenotype. It’s difficult to fully assess the influence of interferon receptor genes alone without the context of all the other genes on chromosome 21, said Dusan Bogunovic, an immunologist at Mount Sinai’s Icahn School of Medicine who was not involved in the work. We just have to go one by one knocking out every extra gene, he said. This also doesn’t give a complete answer because genes work in epistasis with each other; they influence each other.

See also Study points to new role for microglia in Down syndrome

The results reveal that the developmental changes observed in Dp16 mice are triggered by extra copies of the interferon receptor genes; it is not yet known whether these genes have a similar effect in humans. Clinical trials that block interferon signaling can test cause and effect in people, Espinosa said.

These findings also have important implications for the potential effects of interferon signaling on fetal development as they could explain changes in the heart seen in people born to mothers with autoimmune lupus.7

References

- Hultn MA, et al. On the origin of trisomy 21 Down syndrome. Molecular cytogenetics. 2008;1,21.

- Waugh KA, et al. Triplication of the interferon receptor locus contributes to the hallmarks of Down syndrome in a mouse model. Nat Genet. 2023; 55:10341047.

- Damsky W, et al. The emerging role of Janus kinase inhibitors in the treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147(3):814826.

- Barrat FJ, et al. Interferon target gene expression and epigenomic signatures in health and disease. Nat Immunol. 2019; 20(12):1574-1583.

- Sullivan KD, et al. Trisomy 21 constantly activates the interferon response. Avoid. 2016;5:e16220.

- Godfrey M & Lee NR. Memory profiles in Down syndrome through development: A review of memory abilities across the lifespan. J Neurodevelopmental disorder. 2018;10.5

- Vinet, et al. Increase in congenital heart defects in infants born to women with systemic lupus erythematosus: results from the progeny study of the mothers with systemic lupus erythematosus registry. Circulation. 2015; 131(2):149-156.

#Immunity #genes #play #role #syndrome

Image Source : www.the-scientist.com